In 2021, together with Dana Jenei, I compiled a study of this motif including all examples known to me at that date: Dana Jenei & Malcolm Jones, “Woman and the men of the Four Elements” in ed. Dana Jenei, In Honorem Razvan Theodorescu (Bucharest, 2021), 190-204 [available here: https://www.academia.edu/49004926/Woman_and_the_men_of_the_Four_Elements]

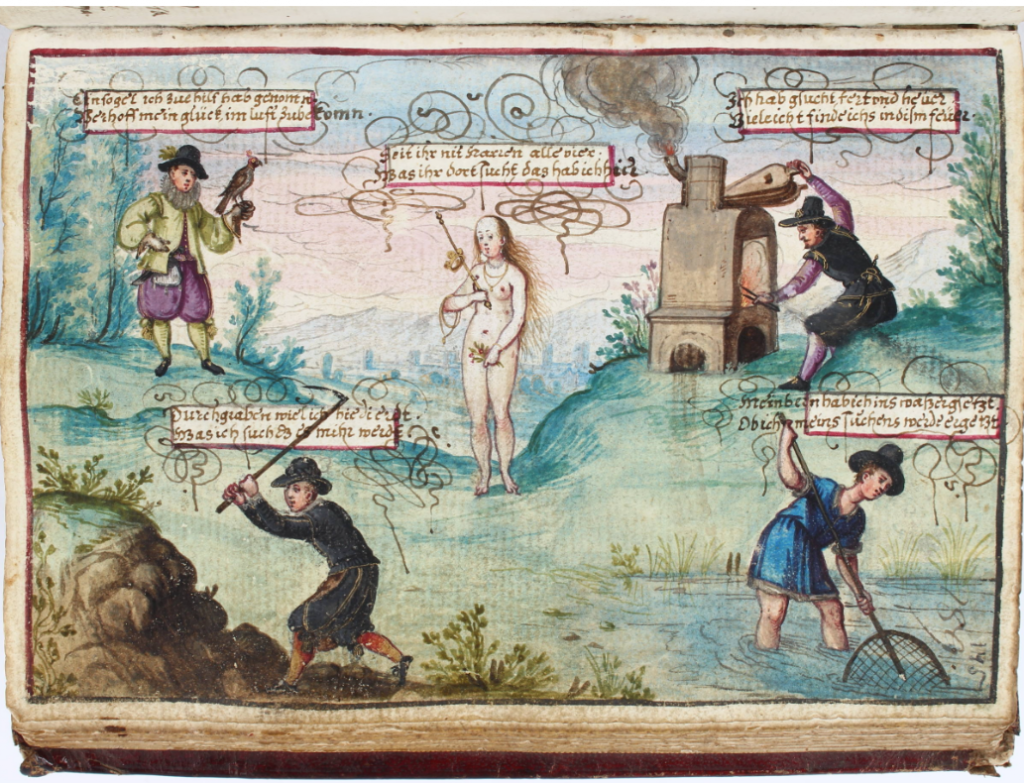

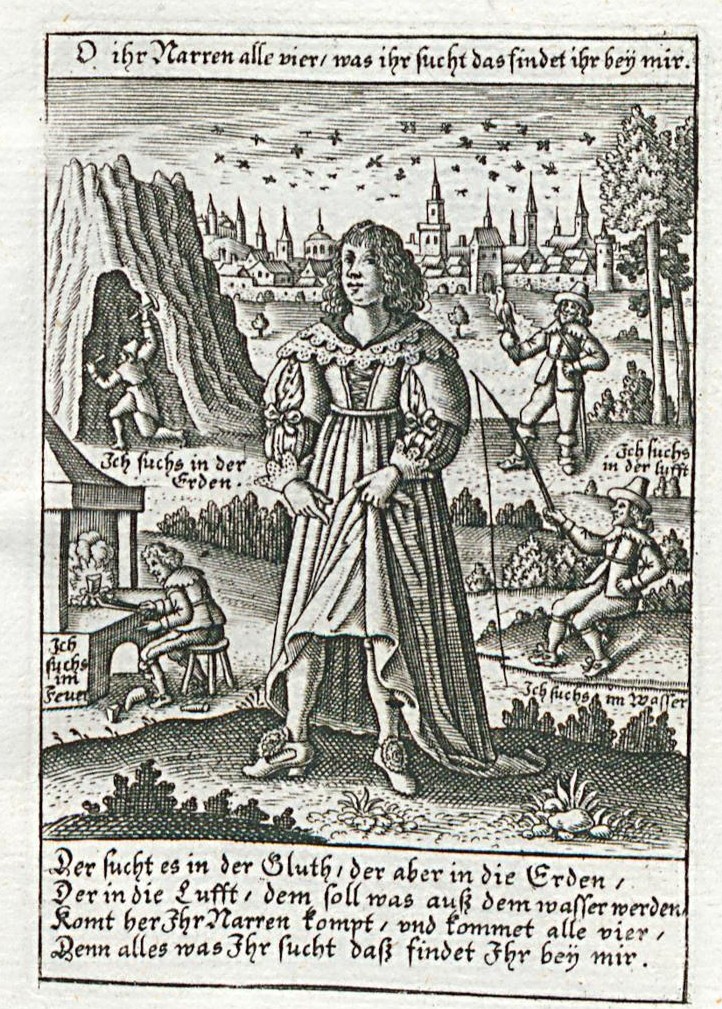

Its popularity in the albums is undoubtedly due to its appearance in the print-books, especially in the editio princeps of the Pugillus Facetiarum (Strasbourg, 1608), but also to the print by Balthasar Jenichen (ante 1579) — BELOW. Another variant featuring a central Venus with 4 putti representing the Elements was published in the Netherlands, probably in the 1590s (BELOW). The often overtly sexual depiction of the motif has led to its ‘censorship’ in more recent times

This post enables me to add a few further examples of the motif to our 2021 listing that have since come to my notice, and especially what is now the earliest — unrecognised when originally published — a remarkable early 16C artefact in a surprising medium — the miniature, engraved silver casing of a micro-carved boxwood prayer-nut, acquired by the Rijksmuseum in 2010 [BK-2010-16] and discussed in the following year’s Bulletin by Frits Scholten. The hemisphere shown here is a mere 2.4 cms high [Photos c/o The Boxwood Project]

Woman: soket vaer ghi vilt hier vindet seek where you will, you find it here [Air] inden loch in the air/hole

Notice how Earth’s gaze is directed at her genitals which she unashamedly outlines with her fingers

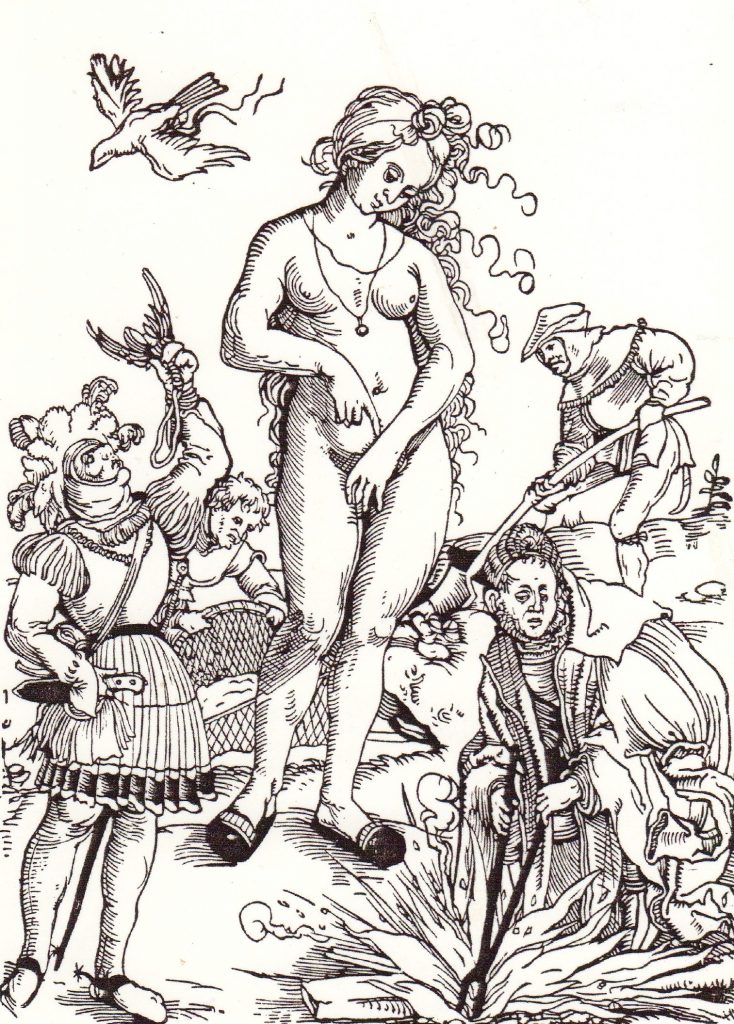

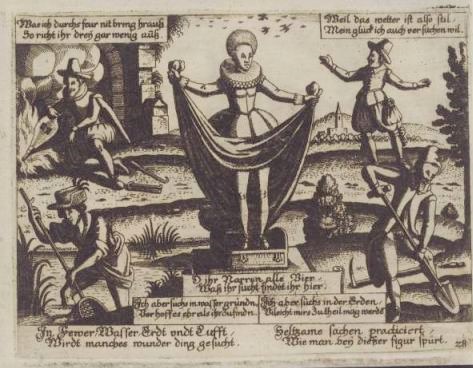

Below is what was previously considered the earliest example of the motif, an impression of a very rare woodcut sheet by Hans Weiditz, conventionally dated to 1521 — it is possible that text has been cropped from top and bottom of the print on account of a perceived obscenity, but if so, must have been the fate of both surviving impressions. Certainly, the explicit nature of the woman’s gesture, pointing unmistakably at her genitals, led several later album owners in which our motif occurs to censor it drastically, by obliteration or excision (see below). From the detailed description given in his extraordinary taxonomic catalogue, it is clear that the early print-collector, Ferdinand Columbus (d.1539), had a copy of our motif — though evidently not the Weiditz [see my essay, “Washing the ass’s head — exploring the non-religious prints” in ed. M. McDonald, The Print Collection of Ferdinand Columbus (London, 2004), 221-245, available here: https://www.academia.edu/42200157/_Washing_the_ass_s_head_exploring_the_non_religious_prints_ ]

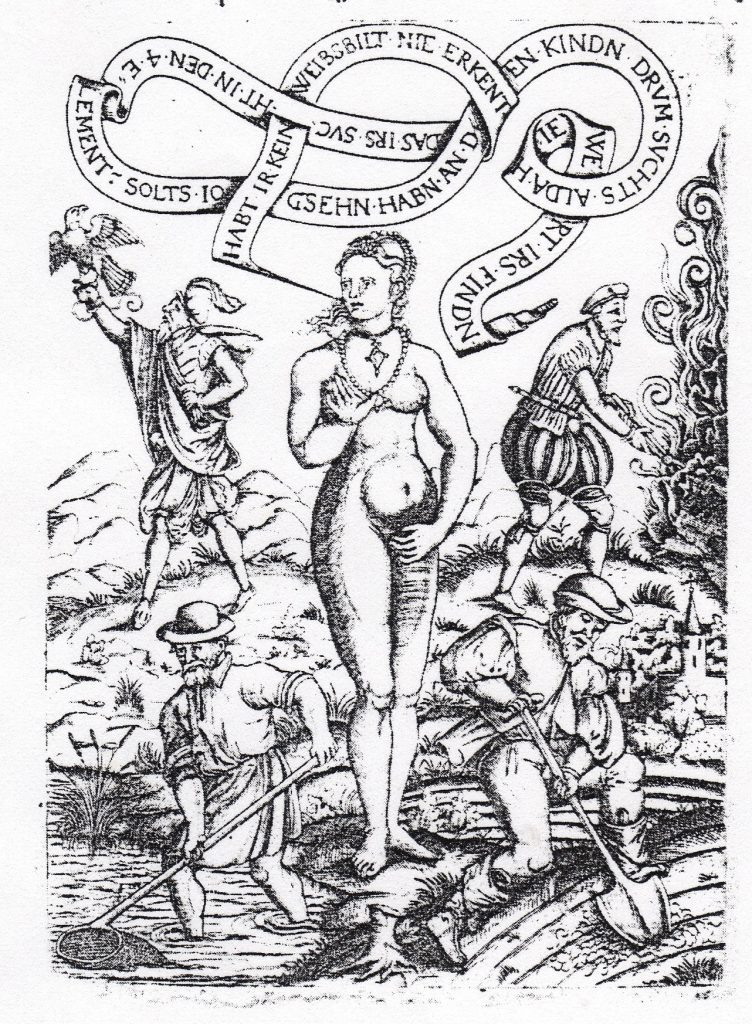

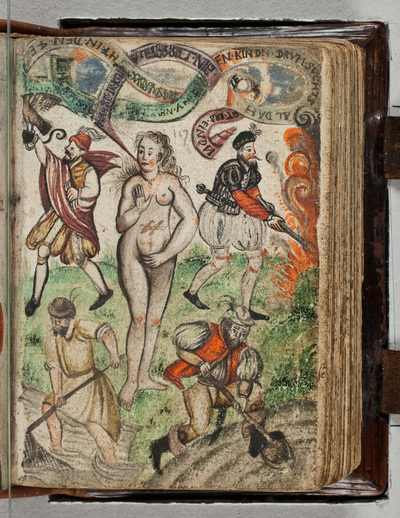

Importantly, this is one of several examples where an album copy provides a terminus ante quem, at least, for an undated print (the Jenichen above). The print was also used as the model to decorate this contemporary glass

This orphaned leaf in the Frommann Collection also looks as if it derives from the Jenichen print, but has been heavily censored by some later owner

Dated 1603 — and thus pre-dating the caption in the Pugillus — this appears to be the earliest occurrence of the derisive verse which was to become standard as a label for this motif (final caption, far right):

O ihr Narren alle Vier O you fools, all four,

Was ihr sucht das hab Ich hier What you seek I have here.

Again, the young woman’s pointing finger leaves us in no doubt as to quite where the ‘here’ of this motif is, and again explains the tendency to find this image censored.

Other prints

The captioning French verses to this print are shockingly direct:

En vain cherches en terre eau ou flamme In vain you search in earth water or fire car c’est a faire au seul trou de madame for it’s only to be found in my lady’s hole

In the Philotheca Corneliana, engraved and published by Peter Rollos in Berlin in 1619, the lady — being herself the treasure — stands in the otherwise empty chest; both her position and the verses of the men of the Four Elements recall the Pusch album image of 1603 (ABOVE). This copy in the Folger Shakespeare Library I assume to be the original edition, the copy in Wolfenbuttel (below) — reversed in respect to this — must be later, as the costume details would seem to confirm.

Unusually, the motif is also found in the sole, dismembered English print-book (London, 1628), etched by Frederik van Hulsen who was working in London in 1627. The captioning text has certainly been toned down, and one might almost describe the image too as bowdlerised for the English market!

Kein Element diss geben kan No element can give (you) this

Was dir hier zeugt der Venus Sohn what Venus’ son shows you here

or — even more baldly — it would be perfectly legitimate to translate zeugt as “points at” here. Like some embarrassing toddler, Cupid points with his forefinger directly at his mother’s crotch.

Other media

The Glucks- or Narren-taler issued by Friedrich Ulrich, Duke of Braunschweig-Luneburg and Prince of Wolfenbuttel, in 1622 and 1624, showed the four men searching in their respective elements on the reverse, and Fortuna (replacing the Woman) on the obverse, with a somewhat kinder version of the familiar mocking rhyme, in that here she addresses the men as ‘people’ [LEUTE] rather than ‘fools’ [NARREN]

This heavily abraded wall-painting in a house in Sibiu, Romania, recently identified by Dana Jenei, is part of a decorative scheme carried out in 1631 and, to date, the only known mural example.

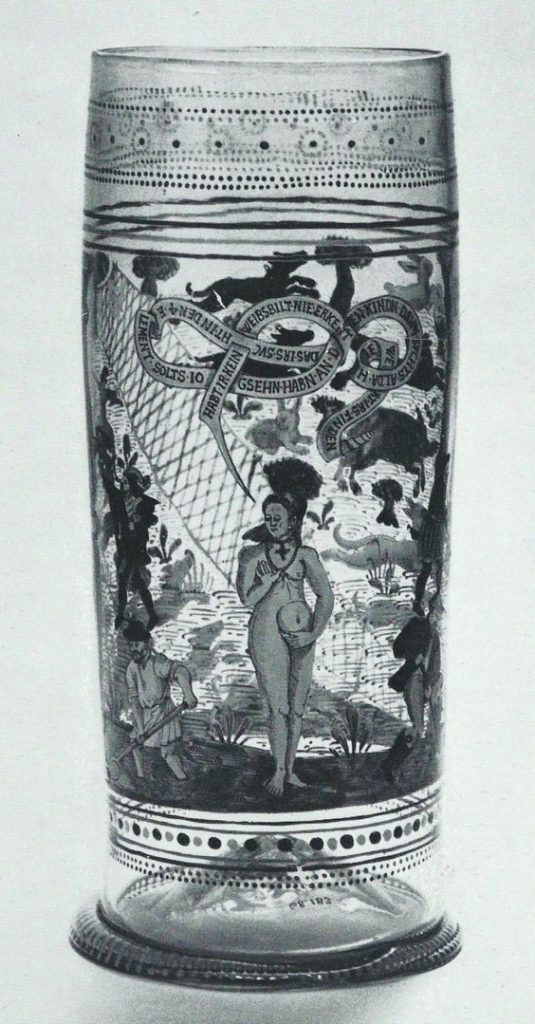

glassware

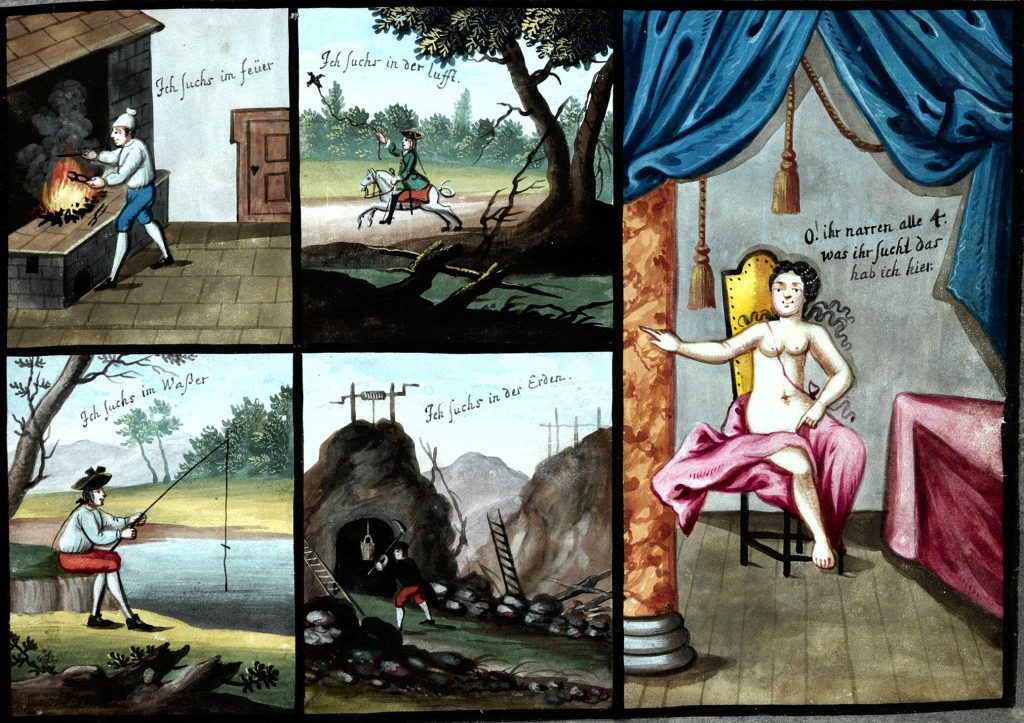

I have reproduced above a Bohemian Humpen enamel-painted in 1584, but the motif remained popular on engraved glass — in the 18C, especially, but a 17C Dutch glass painted with the subject and inscriptions in Dutch is recorded in a book published in 1683. Between the Four Men, says the author, stands a young woman, her hands in front of her apron [haar Hand op haar Voor-schoot] with the familiar mocking inscription below:

Ach! doe Narren alle vier, Was doe zoekst staat immer hier.

(above) This is an 18C Bohemian engraved glass with — as on the Gluckstaler, Fortuna again replacing the Woman, around her medallion, the familiar couplet: O Ihr narren Alle 4 [i.e. vier] / was ihr sucht das hab ich hier. The ‘men’ of the Four Elements are here depicted as putti — thereby inevitably somewhat diluting the starkness of the message — voicing the traditional speeches.

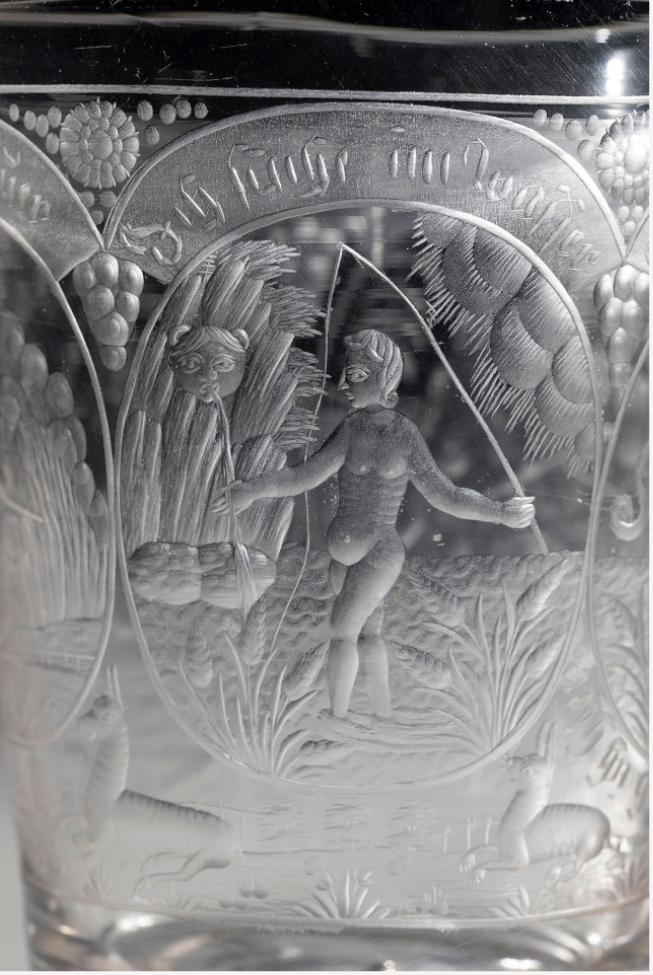

A similar late 17C glass is attributed to the engraver Martin Winter

and below I reproduce from it just one of the men of the Four Elements, a surprisingly naked fisherman — angler, rather, with rod and line — who searches for ‘it’ in Water, saying, Ich suchs im Wasser.

painting

This oil on canvas was painted by Abraham Van der Eyk in 1718 and is now in Schloss Ahlden in Niedersachsen [image via RKD]. The Swiss artist Johann Zick painted another example in the 1750s, but this is now known only from a photograph.

Christianisation

From its earliest appearance the motif would seem to be avowedly secular, the Woman at the centre of a quincuncial arrangement, her sex, her own ‘centric part’ — as Donne styles it in his Elegy 18, Loves Progress — the focus of the ‘displacement activity’ of the four men in their respective elements. It is surprising then to find this same quincuncial arrangement, but with the central figure of the Woman replaced by that of the crucified Christ, on a panel of late 16C Swiss painted glass in the V&A.

?variant

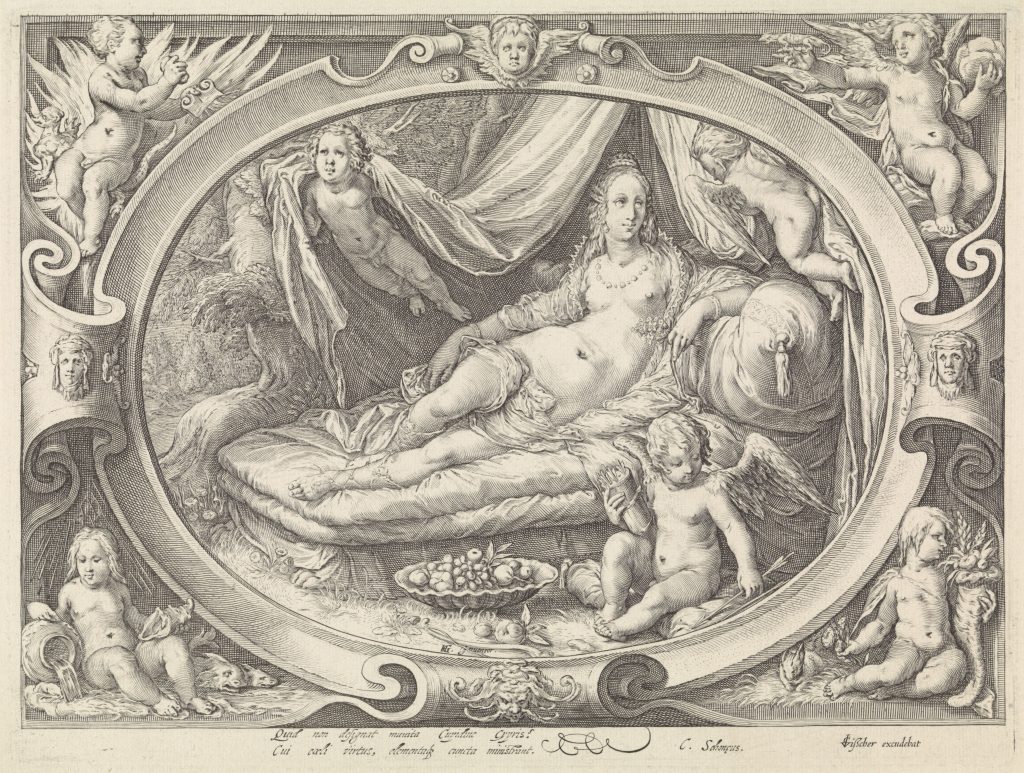

This print was first issued in the Netherlands probably in the 1590s, it was engraved by Jan Saenredam after a design by Hendrik Goltzius. We may render the Latin caption, What cannot Venus fortified by Cupid achieve — she who has power over the heavens and whom all the elements serve! It is perhaps best regarded as a classicising version of our motif the flesh-&-blood men being here replaced by prettified putti

Leave a Reply