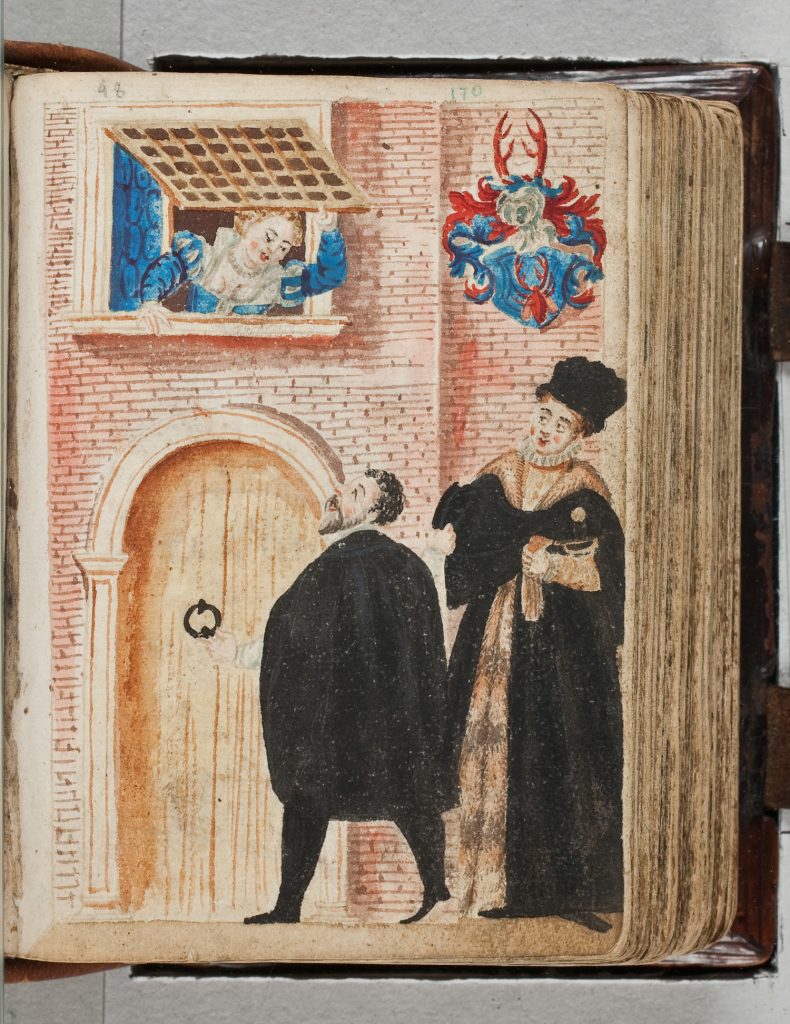

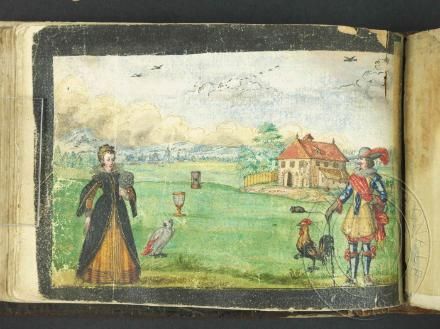

This blog is my attempt to showcase some of the astonishing wealth of imagery to be found in early modern ‘German’ alba amicorum [Stammbucher] — a treasure-house that seems all but unknown to British art historians. My interest is especially in the relationship of these album paintings to the contemporary print repertoire. Sadly, the keeping of such souvenir albums never became a habit in Britain, though occasionally we can show that their imagery was also familiar here. I am hopeful of attracting the attention of German art historians and remain surprised by their seeming lack of interest in these early modern Stammbucher — a recent handsome 2-volume study, for example, while fulsome in its treatment of the social networks amongst album owners, failed almost entirely to discuss the iconography of the albums.

Early Modern Album Amicorum imagery c.1550-1700

(as soon as I can work out how to do it, these few sample images below will be accompanied by commentaries and I hope to be able to work out how to offer a selection of essays on particular motifs in future!)

Explore Early Modern German Albums

Dive into the rich world of alba amicorum, uncovering their artistic and cultural importance in early modern Germany.

Historical Origins

Understand the beginnings and evolution of these friendship books within their historical context.

Iconography and Imagery

Examine the symbolic art and motifs that define these unique personal albums.

Cultural Connections

Discover how these albums reveal social networks and mentalities of the early modern era.

December 2025 Excreting Jesuits

The only painted miniature in the recently digitised album of Gerhard Horst, Hs. 35153 in the Library of the Germanisches Nationalmuseum (dated entries 1607-11) depicts a large devil sitting on a close-stool devouring soldiers and excreting them as priests — a monk sprinkles holy water over the issue. The caption below the image (not shown here) is clearly written — for once! — but not entirely transparent (to me at least! Happy to receive elucidation of the first line from readers!). It reads

fraw Domina, Herz Aley Herz Vicentz, Beneuiste, vitiis (?), Damit das gantze Conuent werde gemehrt

The meaning of the closing German words is clear, at least — ‘so that/thereby the entire convent shall be increased’

[The Provision for the Convent motif — monk smuggles woman into monastery hidden in sheaf of straw — we shall examine on a future occasion]

By this date (1607×11) the motif had already appeared as a single-sheet print in Germany and would appear in several others in the following decade.

late 16C, c.1590 — impression in the Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen.

Pfvh Tevfel Friss Pfaffen Scheiss Landtsknecht [Pooh! Devil eats priests, shits soldiers], shows the Devil in the process of devouring three Jesuit priests and excreting them as soldiers.

Curiously and probably in the 1590s we have a reference to the popularity of this satirical scatological image from an unexpected quarter — in one of the epigrams of Sir John Harington (1561-1612), whose penchant for scatological prints is established by his mention of several in The Metamorphosis of Ajax (1596),[ix] that apotheosis of toilet humour! He had evidently come across a painted version of the present motif which he describes in his posthumously published Epigrams. In the first edition (1615) the poem is entitled How the Deuill eats Fryers, and opens,

The Germans haue a by-word at this howre, In Tabliture[x] by Painters skill exprest, ‘tables’, i.e. paintings, artwork That Sathan dayly Fryers doth deuoure, Which in short time he doth so well disgest, That passing downe to his posterior parts, He souldiers thence vnto the world deliuers... In the 1618 edition the title is changed to Against Church-robbers, vpon a picture that hangs where it is worthy – by which he presumably means in the privy. The by-word is probably Teufel friss[t] Pfaffen schiss[t] Landsknecht ........

The motif of such anal birth was already of some antiquity by this period. It had been graphically used by the Lutherans in 1545 in a series of broadsides with woodcut illustrations by Cranach published at Wittenberg and entitled Abbildung des Papsttums [Depiction of the Papacy]. One sheet, ‘Appearance and Origin of the Pope’, depicts a grinning she-devil who gives birth to the pontiff anally. Another such drastic illustration, contemporary with, but not in fact from that series, entitled ‘On the Appearance and Origin of Monks’, shows that, according to Cranach, they too are born of the Devil — but again, anally. But the Reformation era was not the first time such scatological imagery was employed to satirise the clergy, a misericord in the royal chapel of St. George’s at Windsor Castle, carved c.1480, depicts a friar evacuating a devil accompanied by another friar and devil; this, of course, is, strictly speaking, the reverse of the Cranach illustration, but the effect is much the same. The motif of anal evacuation from a demon can be seen in earlier depictions of hell, such as the late fourteenth-centuty fresco by Taddeo di Bartolo in San Gimignano cathedral, or Giotto’s Last Judgment in the Arena Chapel at Padua, and it was clearly much too good a conception to be allowed to disappear in post-medieval times.

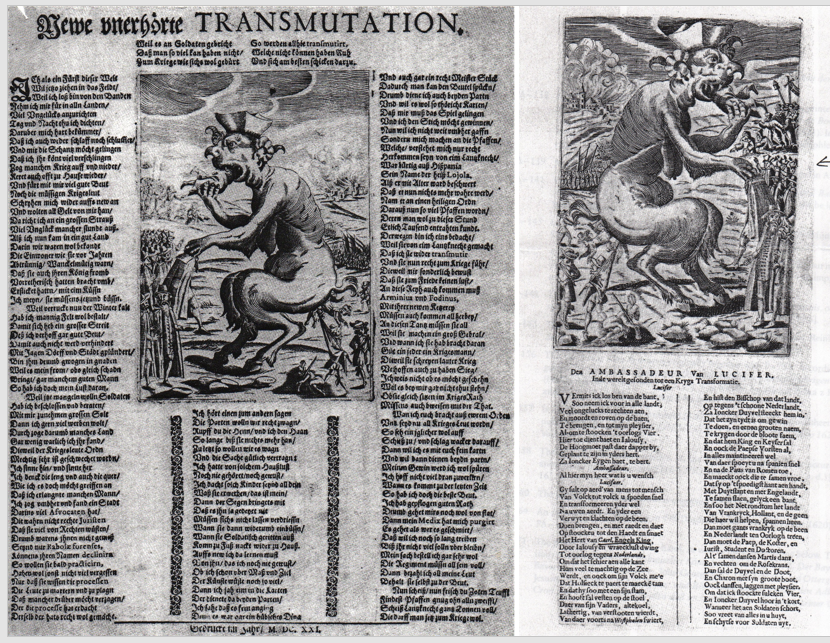

Postdating the album image, are another German broadsheet dated 1621 , entitled the Newe vnerhörte Transmutation [New unheard-of Transmutation], and a related but undated Dutch sheet, Den Ambassadeur Van Lucifer, Inde werelt gesonden tot een Krygs Transformatie),[iv] both clearly deriving their central priest-eating, mercenary-excreting, devil from the earlier German print.

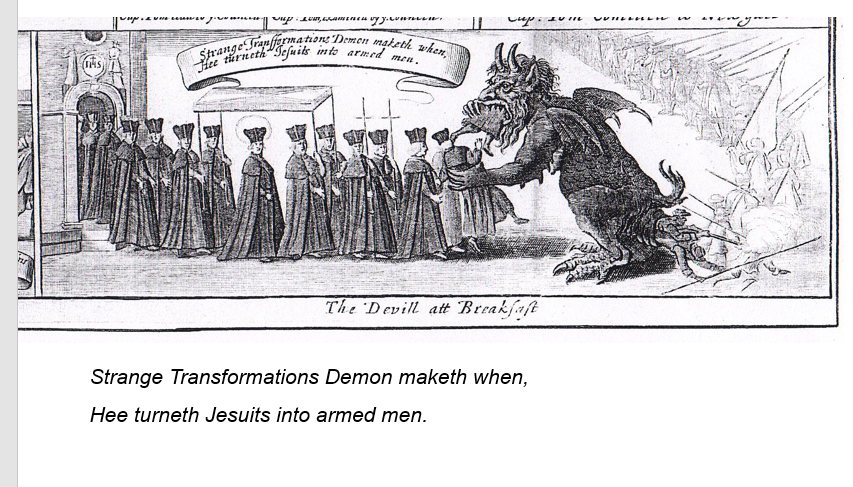

The 1621 sheet further gives its devil a Jesuit’s bonnet, and also includes similarly bonneted Jesuits amongst the men it is about to devour. The motif was eagerly seized upon in Jacobean England and features as the central scene in an English print issued three years later in Amsterdam by the Dutch artist and print-publisher, Claes Jansz.Visscher, surviving uniquely in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. Entitled A Pass for the Romish Rabble, To the Pope of Rome through ye Diuels Arse of Peake (1624), it is a scatological broadside exulting in the (latest) banishment of Jesuits from England.

The title deserves some explanation: despite the literal Devil’s arse that is so instrumental in this operation, the Devil’s Arse of Peake is the earliest-attested name for what is now more genteelly known as the Peak Cavern in Derbyshire, from as early as the ninth century known by this traditional name as one of the mirabilia of Britain.[ii] Interestingly (see further below), it also held a certain fascination for Ben Jonson who alludes to it in his play, The Devil is an Ass (1616), and whose A strange banquet; or, The Devils entertainment by Cook Laurel at the Peak in Devonshire [sic] first appeared as a song in his masque, The Gypsies Metamorphosed, performed in 1621, and — a mark of its popularity — achieved separate publication as a broadside ballad later in the century. In another of Jonson’s poems, An Execration upon Vulcan which, as it was inspired by the destruction of his library by fire in November 1623, must be dated shortly thereafter,[iii] the poet asks Vulcan,

Would you have kept your Forge, at Ætna still, And there made Swords, Bills, Glaves and Armes your fill… Or stay’d but where the Fryar, and you first met, [? Fryar = Roger Bacon] Who from the Divels-Arse did Guns beget…

In A Pass for the Romish Rabble, To the Pope of Rome through ye Diuels Arse of Peake, the distinctive mouth of the cavern itself is recognisable on the horizon, just to the right of the centre of the picture, behind a wayside-cross. The central act is described thus i the verse text below the image:

The Diuel deuoures heere the Iesuites all That they might spue yet their venome & gall, Blurt Mr. Diuel forth he doth shite them, [blurt — an onomatopoeic expression Into braue Drum[m]ers Gunners, & Pikemen of contempt, a ‘raspberry’]

The verse clearly implies that this devil ingests Jesuits and other Catholic clergy, then forth he doth shite them, in the formof soldiers for the conquest of Protestant England. And it is significant that, though not unmistakably depicted as such, i.e. not in the characteristic bonnet, the text of the print regards the men being devoured as Jesuits.

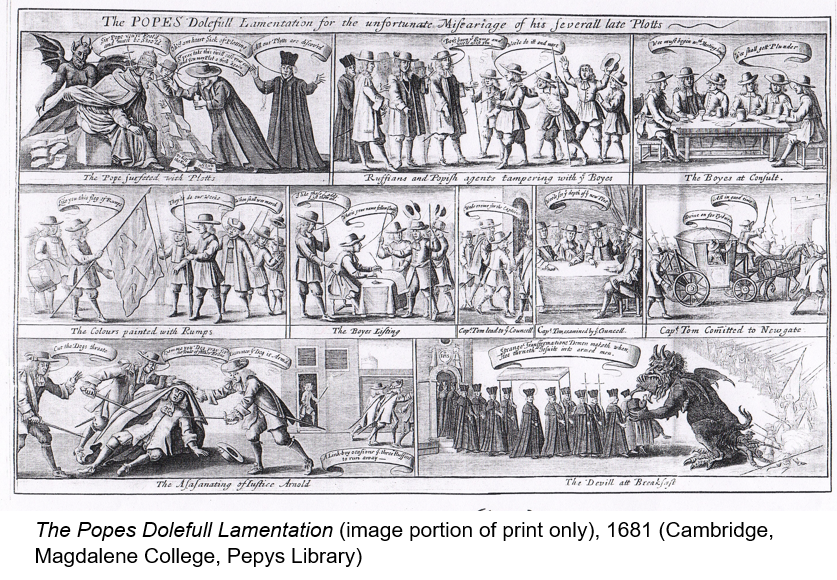

In England this imagery was gleefully re-cycled during the Popish Plot era (1678-80)

BM design for playing card drawn by Francis Barlow BM 1954,0710.4.20 (1678)

[i] James had issued earlier proclamations to the same effect in February 1604, June 1606 and June 1610.

[ii] In the English Latin history known as Nennius, e.g. ed J. Morris, Nennius: British History and the Welsh annals (London, 1980).

[iii] Schanfield 2000.

[iv] Paas 1991, P-678 and PA-145, respectively.

[vi] Larkin and Hughes 1973, no. 252, 591-593.

[x] antedating OED in this ‘artwork’ sense by a century.